Geometria Oculta (Museu Belas Artes de São Paulo - Solo Exhibition)

Our gaze has always been trained to recognize, find patterns, and identify shapes; our thinking, to name, associate, infer, and conclude. This is how we make sense of the world and learn to navigate it—by making it familiar. But there are moments when what presents itself to our senses disorients us and forces us to look twice. Hidden Geometry operates precisely in this ambiguous territory.

See more Geometria Oculta here: https://adobe.ly/3wfnzh7

By Natalia Costa Rugnitz and Daniela Kaplan

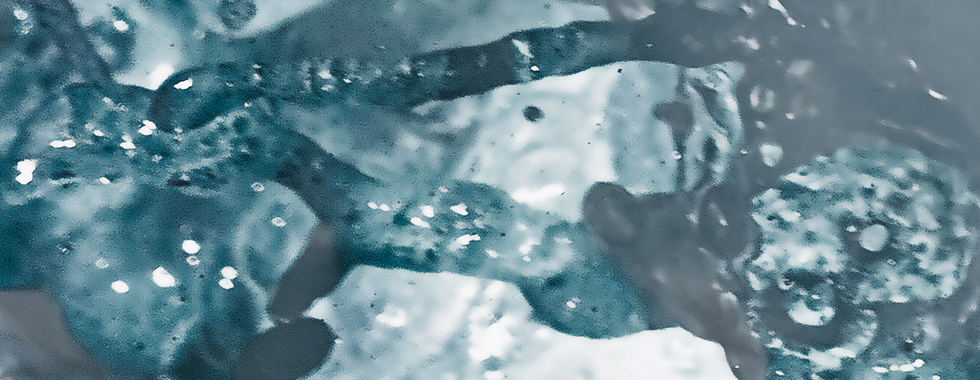

At first glance and from a distance, the works predominantly belong to the realm of abstraction. There is something evocative of action painting: chaotic explosions, intricate textures, juxtaposed chromatic layers, overflow, movement, and freedom. In short, pure expression. The result is a disorder that, far from the Greek aesthetic ideal, possesses the peculiar quality of becoming beautiful.

But upon closer examination, the unsettling emerges. What one sees is, in a way, familiar. But only in a way. We know that there is something real there... yet we cannot pinpoint exactly what. And then, in a sudden instant, the gaze focuses, silhouettes and contrasts take shape, and the discovery is made: it is water. The gratification this produces—a mix of surprise and admiration—generates an almost playful emotional impact. It feels as if we have solved a puzzle.

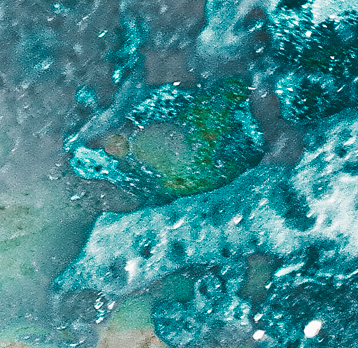

The subject portrayed in this series, let us say it outright, is the raging sea. But the perspective in which it is presented is, for lack of a better term, unusual. The artist reconfigures the sea. He removes it from its context. The sea is and is not the sea because the work dismantles it, fragments it, and thus reveals a new layer of its essence.

As with all great art, the photographs in this selection spark multiple interpretations. The one we choose to emphasize here concerns a material that seems to strive toward becoming geometry.

Indeed, the material takes on spherical configurations or exists in a plastic transition toward them. In the droplets of water suspended in the air—after what we can infer was a violent impact—abstraction begins to give way to figuration at the pace of an advancing geometry.

What is fascinating is that this mixture of chance and intention does not, unlike in dripping, belong entirely to the artist’s gesture but to nature itself. What belongs to the artist is the subtlety of the gaze that allowed him to identify the phenomenon. What is special about his way of seeing that enables him to distinguish, against all inertia, something arcane in the everyday? And how did he then manage to reveal this discovery to the eyes of others? These are reflections on the virtues of the artist’s gaze.

From the viewer’s perspective, when facing works like those in Hidden Geometry, the spontaneous question arises: how was it possible to capture this phenomenon? This applies both to what precedes the practical exercise and to the execution itself. The first challenge in Hidden Geometry is identifying what we are seeing; the second is understanding how the door to this encapsulated world was opened. Let us call this the mystery of technique.

Let us attempt a definition:

Regarding the viewer, we understand the mystery of technique as the subjective state elicited by certain works of art, which consists of an uncertainty about the artist’s process. This is not merely a lack of knowledge about the “steps” taken in the execution of the work: the mystery of technique implies, but is not limited to, an unease regarding the procedures. When we speak of technique, we include the actions or experiences that occur within the artist before the execution of the work. The initial impossibility of understanding the technique—in this dual sense—is not frustrating but seductive, linked to curiosity. Hence the use of the term mystery.

Thus, the mystery of technique is an eminently cognitive phenomenon, for what is curiosity if not the desire to understand? Of course, curiosity has emotional valences, as it carries a component of enthusiasm (and what is enthusiasm if not an emotion?). However, its foundation is not so much sensory impression as the tension generated when thought encounters a difficult limit to cross.

The observer is not drawn into a state of passive contemplation or rest. On the contrary, they are propelled into an essentially intellectual movement, one that perpetuates itself, even if intelligence chooses to sustain itself in the mystery rather than resolve it. In fact, the longer intelligence can linger in this enigma and the deeper the gaze delves into the details of the composition, the more intense and rich the aesthetic experience becomes.

In the case of Hidden Geometry, this is precisely what happens: uncertainty, curiosity, and a consequent desire to know—all infused with a component of fascination.

From a distance, for instance, Venus reveals its aquatic nature more clearly. Here, proximity is the space of mystery. In Rupture, mystery manifests itself much more immediately. Proximity is the space of mystery just as much as distance is.

In Volcano, mystery permeates almost the entire composition.

And all of this intrigues, for it seems inconceivable that the object depicted is the ocean.

This uncertainty, this set of suspicions that coexist with the state of fascination inherent to the mystery of technique, enriches the work and invites us to reflect on the very act of seeing, on our relationship with the visible world, and ultimately, on the complexity that pulses at the core of the universe itself.

In this last sense, a certain vertigo emerges, perhaps similar to the one Borges speaks of. Borges writes:

"The diameter of the Aleph would be two or three centimeters, but cosmic space was there, undiminished in size. Each thing… was infinite things… I saw the populous sea, I saw dawn and dusk, I saw the multitudes of America, I saw a silver web at the center of a black pyramid, I saw a labyrinth… I saw vapor rising from water, I saw… the circulation of my dark blood, I saw the workings of love and the transformation of death, I saw the Aleph, from every point. I saw the earth in the Aleph, and in the earth again the Aleph, and in the Aleph the earth… and I felt vertigo and wept, because my eyes had seen that secret and conjectural object, whose name men usurp, but which no man has ever truly seen: the inconceivable universe."—Jorge Luis Borges (1945)

Geometria Oculta projects a nano perspective of the ocean, where everything seems to be contained within everything else in a kind of "inverted infinity," opening not toward the macro, like the night sky, but toward the micro. Geometria Oculta reveals a microcosm.

This creates a paradox: the works depict something that has always been there, something we know well, yet at the same time, something we had never seen before.

Within this tension lies an unusual richness. And this tension constitutes a significant part of the value of these pieces. For art—and photography in particular—not only reflects the world.

In many cases, it reconfigures it and presents it in dimensions never before explored. Geometria Oculta is one such case.

See more Geometria Oculta here:

.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Natalia Costa Rugnitz holds a Ph.D. and a Master's degree in Philosophy from the University of Campinas (Brazil) and a Bachelor's degree in Humanities from the University of Montevideo. With research periods at Stanford University and Tübingen, her academic background focuses on aesthetics and classical metaphysics, to which she has recently added philosophy of technology and generative art. She is a professor of Digital Ethics at the Catholic University of Uruguay and works as a producer, translator and coordinator in the cultural industry.

Daniela Kaplan is a doctoral candidate in Humanistic Studies at the Pablo de Olavide University (Seville) and holds a master's degree in Art, Museums, and Historical Heritage Management from the same institution. She has a degree in History and teaches History at the University of Montevideo, in addition to a diploma in Art and Culture from the same university. She works in the cultural industry, developing activities in various areas, such as dissemination, production, and editorial coordination. Her recent research focuses on art history, with a special emphasis on visual arts.

***